Ticks: Relevant disease vectors

Nature, fresh air ... and ticks. In recent decades, the number of people and animals affected by tick-borne diseases has increased.

Ticks can transmit bacteria, viruses or parasites which may cause disease in humans and animals. There are multiple reasons for the increased incidence of ticks and tick-borne diseases. For example, climate change, increasing urbanisation and other anthropogenic influences on the ecosystem can contribute to this development.

Together with her team, Professor Dr. Christina Strube, PhD, Head of the Institute of Parasitology at the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover Foundation, aims to determine and provide information about the risk of health hazards posed by ticks and tick-borne diseases. The focus is always on humans and animals: "For us as vets, the animal, its owner and public health form a natural unit," says Professor Strube.

Research on the abundance of ticks, borrelia and other pathogens

Although researchers have already gained substantial knowledge about ticks and the diseases they transmit, the public is often not sufficiently or only inaccurately informed about these topics. "As a result, people often don't know exactly in which regions which tick-borne diseases can occur or how frequently they occur," says Professor Strube. "As a result, they do not always protect themselves and their pets optimally against the small bloodsuckers." Her working group has therefore been regularly analysing ticks for pathogens at various locations in the city of Hanover since 2005. In addition to this long-term monitoring, they determine how frequently ticks occur in Hanover and other regions of Germany (➔). They were able to show, for example, that the infection rate of ticks with Borrelia (➔) and Anaplasma (➔) has remained largely constant over the years in the city of Hanover, while infection rates with Rickettsiae (➔) show considerable fluctuations.

The tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) virus is also among the health hazards posed by ticks. Although the virus is predominantly found in southern Germany, its presence was proven at five different locations in Lower Saxony in cooperation with the Lower Saxony State Health Office and the National Consiliary Laboratory for TBE (➔). The testing of animals for TBE antibodies also contributes to a better understanding of the spread of the virus in Lower Saxony (➔).

© Institut für Parasitologie, TiHo

Climate change and other human influences lead to the spread of ticks

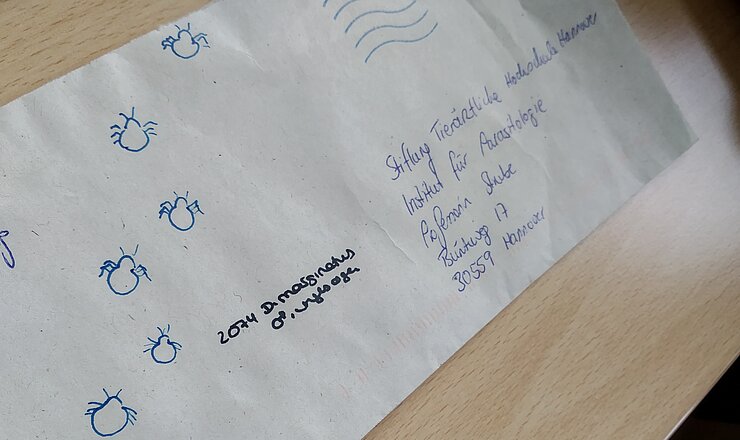

Not only pathogens, but also the ticks themselves are becoming increasingly widespread. This is particularly evident in the case of the ornate dog tick Dermacentor reticulatus, also known as the meadow tick. This tick species is now widespread throughout Germany, as has been shown by submissions from committed citizens (➔). As the submission of ticks continued even after the period of the appeal, it was possible to provide more precise maps of the spread of the meadow tick and to show the current distribution throughout Germany using forecast models (➔).

With the support of veterinary practices throughout Germany, Professor Strube and her team were also able to show that the meadow tick Dermacentor reticulatus is now the second most common tick in dogs after the castor bean tick Ixodes ricinus; in Saxony-Anhalt and Brandenburg, it is now even the most common tick species found on dogs (➔).

Due to the climate crisis, average temperatures have been rising continuously throughout the year for decades. The mild winters and the associated sparse or often complete lack of snowfall influence tick activity (➔). According to the German Weather Service, the average winter temperature during the months of December to February was up to 3.1 degrees Celsius higher in recent years compared to the climatic reference period from 1961 to 1990. As part of a one-year submission study, almost 20,000 ticks were used to document how many castor bean ticks and meadow ticks had bitten dogs and cats in the winter months. The meadow tick is constantly active throughout the winter - except when it snows. Additionally, the common castor bean tick is now also active in mild winters from December to February. In particular, a significant activity increase of both tick species was observed in February (➔).

© Institut für Parasitologie, TiHo

Life-threatening animal pathogens

Canine babesiosis, which is transmitted by the meadow tick Dermacentor reticulatus, poses a particular threat to dogs. Babesia are single-celled parasites that attack and destroy red blood cells, which can lead to anaemia. Despite intensive treatment, the disease is often fatal. Unfortunately, the rapid spread of the meadow tick in Germany has already led to an increase in cases of babesiosis in dogs (➔). Professor Strube and her team were recently able to show that not only dogs subclinically infected with Babesia, which are brought to Germany from other European countries via animal welfare organisations, contribute to the spread of the pathogen, but that also dogs travelling within Germany may carry Babesia-positive meadow ticks with them. Domestic dogs can therefore also be the cause of new foci of infection for canine babesiosis in Germany (➔). Professor Strube summarises the results of her research as follows: "Due to this spread of vector ticks, especially in conjunction with the current winter activity of ticks, it is important to protect dogs with an effective anti-tick product throughout all months of the year - not only to protect your own dog, but the entire domestic dog population".

In addition to canine babesia, bovine babesia are also native to Germany. However, they are transmitted by the castor bean tick Ixodes ricinus. Bovine babesia can also lead to serious disease and death, although outbreaks in cattle are rare in Germany nowadays. Nevertheless, they can occur unexpectedly and be accompanied by high animal losses, as shown by a case in a cattle herd in northern Germany (➔), which was monitored and analysed epidemiologically by Professor Strube and her team in collaboration with other TiHo scientists (➔).

Interdisciplinary co-operation

There may also be knowledge gaps or other weaknesses in the healthcare system, resulting in inadequate prevention, delayed diagnosis or incorrect treatment of diseases transmitted by ticks. "We need an efficient risk assessment and effective prophylactic measures as well as optimised tests to rapidly and more precisely detect tick-borne pathogens. And we need an optimal management of tick-borne diseases," says Professor Strube. "By exchanging and pooling data and information with researchers from the fields of human medicine, biology and other disciplines, we can jointly contribute to the best possible protection of human and animal health in line with the One Health concept." A review article on the diagnosis of tick-borne diseases in human and veterinary medicine (➔) and a comparative analysis of the occurrence of tick-borne zoonotic pathogens in pets in temperate and cool regions of Europe (➔) also contribute to this.

In addition to cooperating with fellow scientists, Professor Strube's group is also working with the Lower Saxony State Health Office and the National Consiliary Laboratory for Tick-borne Encephalitis (TBE) to investigate the occurrence of TBE in Lower Saxony. Together, they were able to report on infected ticks at five locations in Lower Saxony (➔). There is also a long-standing and close collaboration with the National Reference Centre for Borrelia, with which, for example, the correlation between tick age and Borrelia infection status was investigated (➔).

© Institut für Parasitologie, TiHo

Networking is also reflected in transnational projects. For example, eleven partners from the countries bordering the North Sea - Sweden, Denmark, Norway, the UK, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany - joined forces for the "NorthTick" project. There is also a collaboration with the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu) and researchers from the University of Amsterdam and the University of Aberdeen (UK).

Dissemination of information to the public

"We would like to pass on the results of our investigations and possible preventative measures to the public and often also specifically to pet owners or the veterinary profession," says Professor Strube.

This starts with the youngest children - for example, ticks were a topic at the children's university Hannover (KinderUniHannover). Professor Strube asked "Do you have to be afraid of ticks?" and took the children on a journey through a tick's life to answer this question, while explaining how they can protect themselves from a tick bite. The event also attracted a lot of media attention in the region, with some of the young listeners proudly appearing in various online and print media the next day.